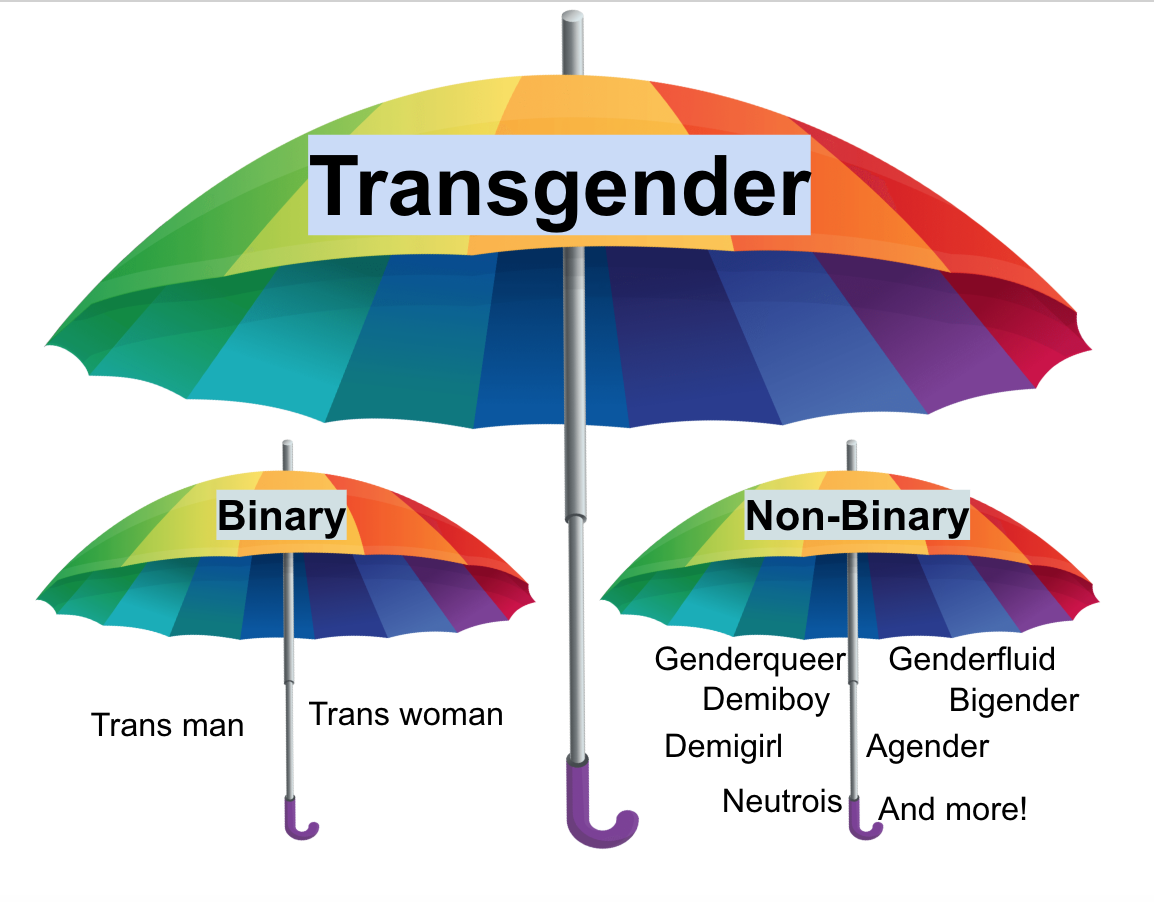

And the next step on the path to liberation is the recognition of a new range of gender identities: so we now have people referring to themselves as ‘genderqueer’ or ‘non-binary’ or ‘pangender’ or ‘polygender’ or ‘agender’ or ‘demiboy’ or ‘demigirl’ or ‘neutrois’ or ‘aporagender’ or ‘lunagender’ or ‘quantumgender’… I could go on. Humans of both sexes would be liberated if we recognised that while gender is indeed an internal, innate, essential facet of our identities, there are more genders than just ‘woman’ or ‘man’ to choose from. On this view, which for ease I will call the queer feminist view of gender, what makes the operation of gender oppressive is not that it is socially constructed and coercively imposed: rather, the problem is the prevalence of the belief that there are only two genders.

Such people not only dispute that gender is entirely constructed, but also reject the radical feminist analysis that it is inherently hierarchical with two positions. This view of the nature of gender sits uneasily with those who experience gender as in some sense internal and innate, rather than as entirely socially constructed and externally imposed. So, for the radical feminist, the aim is to abolish gender altogether: to stop putting people into pink and blue boxes, and to allow the development of individuals’ personalities and preferences without the coercive influence of this socially enacted value system. Understood like this, it’s not difficult to see what is objectionable and oppressive about gender, since it constrains the potential of both male and female people alike, and asserts the superiority of males over females. This value system, and the process of socialising and inculcating individuals into it, is what a radical feminist means by the word ‘gender’. From then on, they will be inculcated into one of two classes in the hierarchy: the superior class if their genitals are convex, the inferior one if their genitals are concave.įrom birth, and the identification of sex-class membership that happens at that moment, most female people are raised to be passive, submissive, weak and nurturing, while most male people are raised to be active, dominant, strong and aggressive. Individuals are born with the potential to perform one of two reproductive roles, determined at birth, or even before, by the external genitals that the infant possesses. Not only are these norms external to the individual and coercively imposed, but they also represent a binary caste system or hierarchy, a value system with two positions: maleness above femaleness, manhood above womanhood, masculinity above femininity. On this view, which for simplicity we can call the radical feminist view, gender refers to the externally imposed set of norms that prescribe and proscribe desirable behaviour to individuals in accordance with morally arbitrary characteristics. It used to be a basic, fundamental feminist idea that while sex referred to what is biological, and so perhaps in some sense ‘natural’, gender referred to what is socially constructed. For feminists, this distinction has been important, because it enables us to acknowledge that some of the differences between women and men are traceable to biology, while others have their roots in environment, culture, upbringing and education – what feminists call ‘gendered socialisation’.Īt least, that is the role that the word gender traditionally performed in feminist theory.

But since at least the 1960s, the word has taken on another meaning, allowing us to make a distinction between sex and gender. The word ‘gender’ originally had a purely grammatical meaning in languages that classify their nouns as masculine, feminine or neuter. Perhaps due to a vague squeamishness about uttering a word that also describes sexual intercourse, the word ‘gender’ is now euphemistically used to refer to the biological fact of whether a person is female or male, saving us all the mild embarrassment of having to invoke, however indirectly, the bodily organs and processes that this bifurcation entails. In everyday conversation, the word ‘gender’ is a synonym for what would more accurately be referred to as ‘sex’. What is gender? This is a question that cuts to the very heart of feminist theory and practice, and is pivotal to current debates in social justice activism about class, identity and privilege.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)